Abandon ill will,

Thoughts of self instilled.

Then the mind set still.

Ideas realized

Abandon ill will,

Thoughts of self instilled.

Then the mind set still.

smile (verb): form one’s features into a pleased, kind, or amused expression.

“Bodhicharyāvatāra”

by Shantideva

Chapter 5, Attentiveness:

71.

Be the master of yourself

And have an ever-smiling countenance.

Rid yourself of scowling, wrathful frowns,

And be a true and honest friend to all.

“The Bodhisattva Guide”

commentary by H.H. The Dalai Lama:

“True practitioners are unaffected by external pressures and their own emotions, and they are free to secure the temporary and ultimate benefit of both themselves and others. They remain independent, fear nothing, and are never at odds with themselves. Always peaceful, they are friendly with all, and everything they say is helpful. Wherever we go, let us be humble and avoid being noisy or bossy. Let us not hurt other people’s feelings or cause them to act negatively. Rather, let us be friendly and think well of others, encouraging them to accumulate positive actions….”

“Whatever we say, let us speak clearly and to the point, in a voice that is calm and pleasant, unaffected by attachment or hatred. Look kindly at others, thinking, it is thanks to them that I shall attain Buddhahood.”

Perceiver’s mind

Transient transceiver,

To

Conscious, Awareness,

Abiding aether.

dhyāna. (Pali: jhāna; Tibetan: bsam gtan; Chinese: chan/chanding; Japanese: zen/zenjō; Korean: sŏn/sŏnjŏng 禪/禪定). In Sanskrit, “meditative absorption,” specific meditative practices during which the mind temporarily withdraws from external sensory awareness and remains completely absorbed in an ideational object of meditation. The term can refer both to the practice that leads to full absorption and to the state of full absorption itself. Dhyāna involves the power to control the mind and does not, in itself, entail any enduring insight into the nature of reality; however, a certain level of absorption is generally said to be necessary in order to prepare the mind for direct realization of truth, the destruction of the afflictions (KLEŚA), and the attainment of liberation (VIMUKTI).

Dhyāna is classified into two broad types:

Each of these two types is subdivided into four stages or degrees of absorption, giving a total of eight stages of dhyāna. The four absorptions of the realm of subtle materiality are characterized by an increasing attenuation of consciousness as one progresses from one stage to the next.

The deepening of concentration leads the meditator temporarily to allay the five hindrances (NĪVARAṆA) and to put in place the five constituents of absorption (DHYĀNĀṄGA).

The five hindrances are:

These hindrances thus specifically obstruct one of the specific factors of absorption and, once they are allayed, the first level of the subtle-materiality dhyānas will be achieved. In the first dhyāna, all five constituents of dhyāna are present; as concentration deepens, these gradually fall away, so that in the second dhyāna, both types of thought vanish and only prīti, sukha, and ekāgratā remain; in the third dhyāna, only sukha and ekāgratā remain; and in the fourth dhyāna, concentration is now so rarified that only ekāgratā is left.

Detailed correlations appear in meditation manuals describing specifically which of the five spiritual faculties (INDRIYA) and seven constituents of enlightenment (BODHYAṄGA) serves as the antidote to which hindrance. Mastery of the fourth absorption of the realm of subtle materiality is required for the cultivation of the supranormal powers (ABHIJÑĀ) and for the cultivation of the four ārūpyāvacaradhyānas, or meditative absorptions of the immaterial realm. The immaterial absorptions themselves represent refinements of the fourth rūpāvacaradhyāna, in which the “object” of meditation is gradually attenuated.

The four immaterial absorptions instead are named after their respective objects:

Mastery of the subtle-materiality realm absorptions can also result in rebirth as a divinity (DEVA) in the subtle-materiality realm, and mastery of the immaterial absorptions can lead to rebirth as a divinity in the immaterial realm. Dhyāna occurs in numerous lists of the constituents of the path, appearing, for example, as the fifth of the six perfections (PĀRAMITĀ).

from: “The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism”

Distinct thoughts cannot

Occupy same mind

Concurrent in time.

It is when chained,

As kind proclaimed,

“I” ascertained.

from “Tara’s Enlightened Activity”

by Khenchen Palden Sherab and Khenpo Palden Sherab

Part One “Nobel Lady Tara in Tibetan Buddhist Life“

subsection “Understanding Tara at the Ultimate Level” excerpts herein

At all levels, from the Hinayana up through the Vajrayana, Buddha Shakyamuni used the language of the Great Mother to explain the ultimate true nature. In fact, at their core, all the teachings of the buddhas are none other than explanations of the nature of the Mother. She is given several different titles, such as Mother of all the Buddhas and Mother of all Samsara and Nirvana.

The ultimate nature is correctly described as our true Mother because she is that which gives birth to and develops our own enlightened mind. For a long time our obscured minds have been distanced from our original nature. Therefore, we wander in samsara lost and confused.

Buddha is the one who really points out the way back home and reintroduces us to our own true Mother.

Until now we have been distracted and separated from the recognition of absolute reality, the Mother true nature.

Throughout the sutras and tantras of the Mahayana Prajnaparamita and the Dzogchen, the Buddha taught that we must reconnect ourselves with this Mother. In her ultimate state she is none other than the tathagatagarbha [‘Buddha nature’ (Tib. kham / rig)].

Joy, peace, and enlightenment will come when we reconnect ourselves with our true nature. To provide the opportunity for beings to do this, the Mother herself has emanated in many different sambhogakaya and nirmanakaya forms.

The specific practice we are discussing is called the Twenty-one Praises to Tara. Here we see twenty-one different Taras, with different names, colors, and so forth… The number twenty-one has specific symbolic meanings. At the basic level the Buddha taught twenty-one techniques with which we may work to attain enlightenment.

According to the Mahayana sutra system, as we practice we traverse the ten different levels, or bhumis, eventually reaching the enlightened state. The basis for our enlightenment is right where we find ourselves now, with the precious endowment of our own human body and our own buddha-nature.

Vajrayana, or tantra, is similar to the sutra system, but its methods are more specifically targeted. According to tantric teaching, within this human body we have twenty-one different knots. These are in pairs and they obstruct or block our channels. Through practice, as we release each of these pairs of knots, we obtain a specific experience or realization. After we have released all of the twenty-one knots, we are known as enlightened beings, having attained buddhahood.

Of course, buddhahood is not some force that is outside us, waiting for the knots to be untied in order to come in. From basic Buddhism all the way to Dzogchen, it is made perfectly clear that buddhahood is an innate state, already within us. Our inherently awakened state is an already enlightened being, a buddha, the tathagatagarbha. When we release those twenty-one knots, we attain the ultimate awakening known as the dharmakaya state.

The dharmakaya, in turn, has twenty-one spontaneously inherent qualities. They transcend duality, the compounded state, permanence and impermanence, and effort or striving. Unceasingly they arise as necessary for the benefit of all sentient beings. These twenty-one active dharmakaya qualities appear as the twenty-one emanations of Tara.

Thus Tara combines all the active energies of the three kayas by which we release our own knots and those of other beings, the energy by which we achieve enlightenment and help other beings to achieve it.

As the embodiment of enlightened energy, Tara is inseparable from the wisdom dakini [ ‘Sky-goer’ (Skt. ḍākinī; Tib. khandroma)]… An expanded meaning of dikini would be “the activity of love and compassion, full of strength, moving freely in the wisdom space.

As we turn our attention to the wisdom dakini nature of Tara, this will bring us into a consideration of the deep meaning of the true nature of our minds and of reality. When we begin to study and practice and we start looking beyond externals to internal levels, we know intellectually there will be much to discover. Initially we can’t penetrate deeper levels very well because our present consciousness and senses are deluded by habitual patterns of conceptual and dualistic thinking.

No matter how carefully and openly we try to look and think about things, our view is always partial, limited. That’s just how our mental habits have developed. Of course, what we’re able to see now, limited though it is, seems to fulfill our everyday needs so we don’t think there’s anything wrong with it.

But then, inspired by the teachings, we do try to look deeper. At first we find we’re unable to perceive any reality beyond our habitual pattern, even though we have adequate eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mental capacities. The perceptions of our six senses are trapped by our old attitudes of partiality and limitation. We’re always setting up rules and mental boundaries. Once we start to take note, we’ll see that we entrap ourselves in every direction with a web of concepts. Skillful and determined practice is needed in order to break the pattern and see beyond. Once that happens, our wisdom mind sees the true nature of reality as vastness from which arises an unceasing display of dynamic forms called the display of the mandala of the wisdom dakinis.

That’s why the great masters teach about developing the openness state symbolized by the dakin’s third eye. Her third eye, or wisdom mind, sees beyond duality. For the wisdom mind there are no boundaries or limitations. For example, an individual with the realization of the wisdom mind makes no distinction between past, present, and future. All are seen in one instant.

Our wisdom must be developed inwardly; it has nothing to do with external conditions. Our dualistic minds have also developed inwardly; we are internally obscured. The mind’s true nature is always buddha-nature and its experience is perfect joy and peace.

This understanding will develop according to our stage of realization. To the extent that we cleanse our minds of habitual patterns, we become more able to see the clear image of absolute truth. …As we gradually clear out our internal habitual patterns, our understanding becomes clear.

Realizations come only if we practice joyfully, with confidence and courage. Realization doesn’t grow within a timid or weak state of mind — it blossoms in the mind free of doubt and hesitation. Realization is fearless. When we see the true nature of reality, there’s nothing hidden, nothing left to fear. At last we’re seeing reality as it is, full of joy and peace.

Our habitual patterns can only be removed by understanding the great emptiness aspect of true nature, that which is named the Mother of all the buddhas. Emptiness is freedom; emptiness is great opportunity. It is pervasive and all phenomena arise from it. As the great master Jigme Lingpa said, “The entire universe is the mandala of the dakini.” The Mother’s mandala is all phenomena, the display of the wisdom dakini.

Without this ultimate great emptiness, the Mother of the buddhas, the universe would be without movement, development, or change.

Because of this great emptiness state of the Mother, we see phenomena continually arising. Each display arises, transforms, and radiates, fulfilling its purpose and then dissolving back into its original state. This dramatic dance of energy is the activity, ability, or mandala of the wisdom dakini. Thus, the combination of the great emptiness or openness state, together with the activities of love and compassion, is both the ultimate Mother and the ultimate wisdom dakini.

This ultimate nature of reality is not separate from the nature of the mind. We should not disconnect them. When we look into our own mind, we see that it’s also based on this great emptiness wisdom state.

We won’t find anything substantially existing because this Mother is beyond conceptions and habit patterns. Yet our thoughts and conceptions, which are mental phenomena, continually arise from the mind’s true nature, each thought fulfilling its own purpose, then dissolving back into the original state. There are no solid entities at all, just an unceasing display of dynamic form; as it is called for, it appears. That is how mind is the display of the mandala of the wisdom dakinis.

Try not to spoil this arising energy of love and compassion of the wisdom dakini with ego-clinging. Ego is duality; ego-clinging or grasping is an obscuration that disturbs the radiating energy of the wisdom dakini. It also disturbs our practice, so we must try to release it, or at least ease it, by developing more love, compassion, and openness. This is the essence of Dzogchen and of the Buddhadharma.

[Emptiness] is a state full of freedom and opportunity. It is the pervasive nature of every external and internal sense object and the source of every outer and inner display. As the Heart Sutra says, “Emptiness is form; form is emptiness. Emptiness is none other than form; form is none other than emptiness.” Furthermore, emptiness is the source of our minds. Mind resides totally within this great emptiness state. Try as we might, we cannot grasp our own mind. That is as useless as grasping at the sky.

A brief summary of the essential teachings of Tibetan Tantra is given [herein].

It goes without saying that this brief summary is less than adequate to represent the vast and comprehensive contents of the Tibetan Tantra.

One cannot expect, therefore, to glean from these brief lines more than a hint of the essential, underlying principles.

Tibetan Tantrism is a form of practical Buddhism abounding in methods and techniques for carrying out the practice of all the Mahãyana teachings. In contrast to the “theoretical” forms of Buddhism… Buddhist Tantrism lays most of its stress on practice and Realization, rather than on philosophical speculations. Its central principles and practices may be summarized as follows:

(1) The Path of Means: The main practices of the Path of Means contain the following eight steps:

(2) The Path of Liberation, or the Yoga without Form, is the simplest and most direct approach toward the Buddha-Mind. It is a natural and spontaneous practice, bypassing many preparations, strenuous exercises, and even successive stages as laid down in other types of Yoga. Its essence consists in the Guru’s capability of bringing to his disciple a glimpse of the Innate Buddha-Mind in its primordial and natural state. With this initial and direct “glimpsing experience,” the disciple gradually learns to sustain, expand, and deepen his realization of this Innate Mind. Eventually one will consummate this realization to its full blossoming in Perfect Enlightenment. This practice is called Mahamudra.

Paradoxically, effortlessness is even more difficult to achieve than relaxation. It requires long practice to become “effortless” at all times and under all circumstances. If one can keep their mind always relaxed, spontaneous, and free of clinging, the Innate Buddha-Mind will soon dawn.

(3) The Path of Means and The Path of Liberation, exist only in the beginning stages. In the advanced stages these two Paths converge and become one. It is to the advantage of a yogi, in order to hasten spiritual progress, to either practice both teachings at the same time or use one to supplement the other. Most of the great yogis of Tibet practiced both Paths, as did Milarepa.

…

Continue reading “The Path of Means and Of Liberation (in brief)”

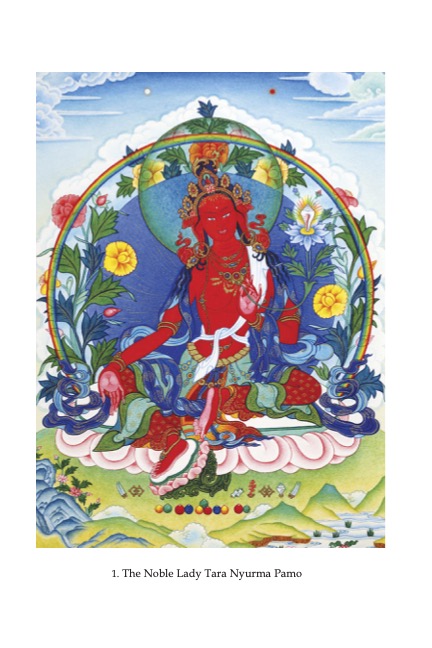

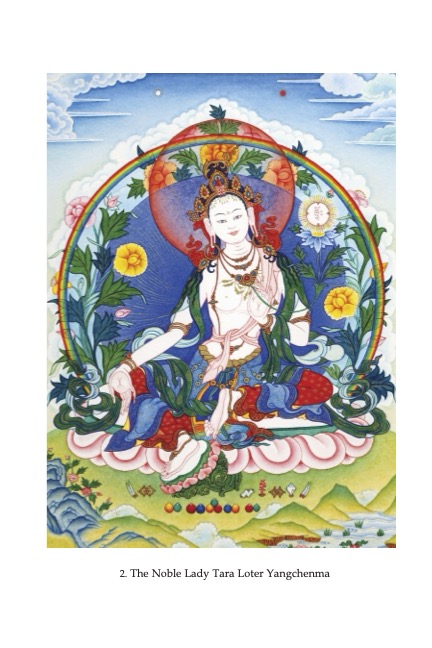

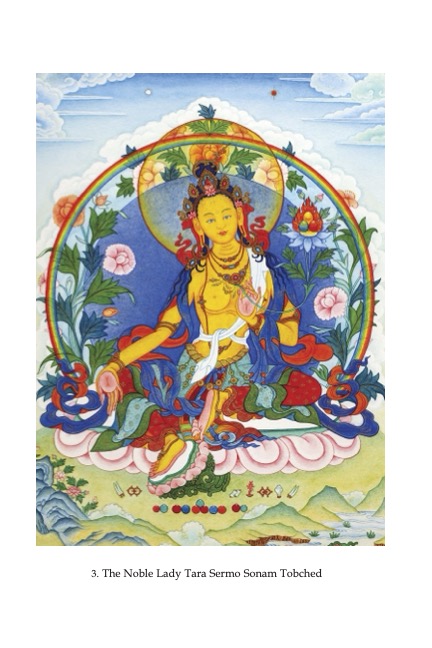

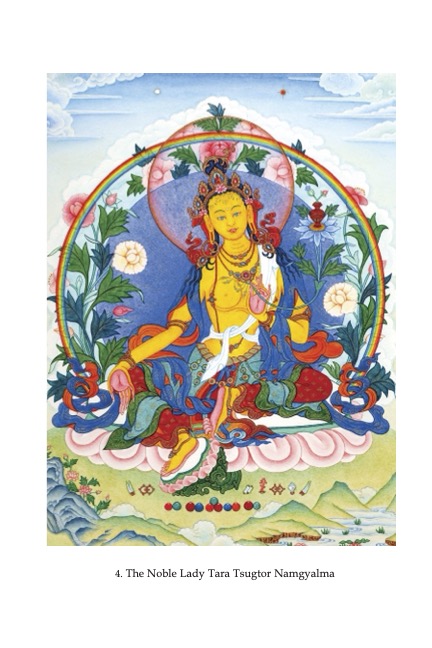

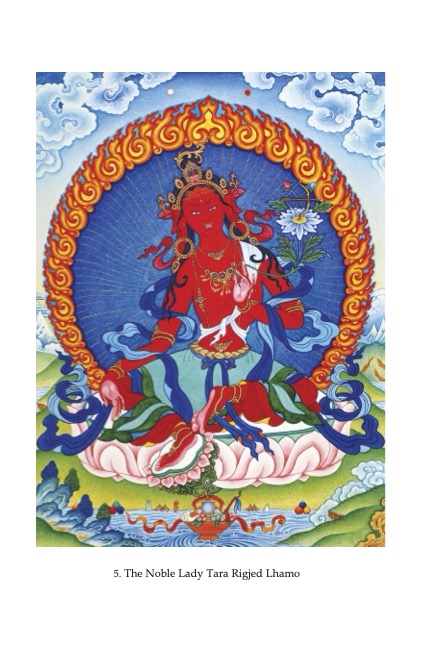

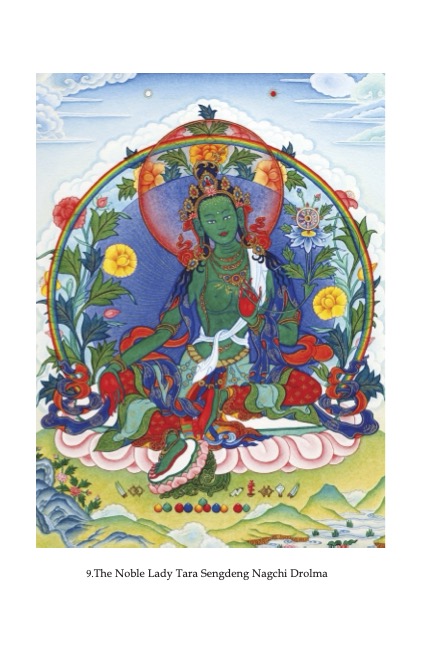

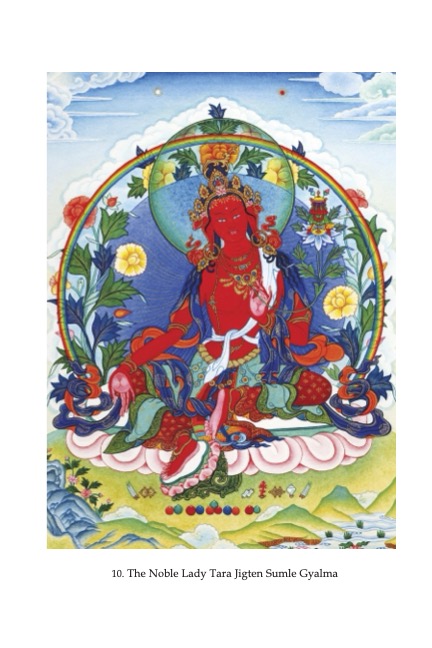

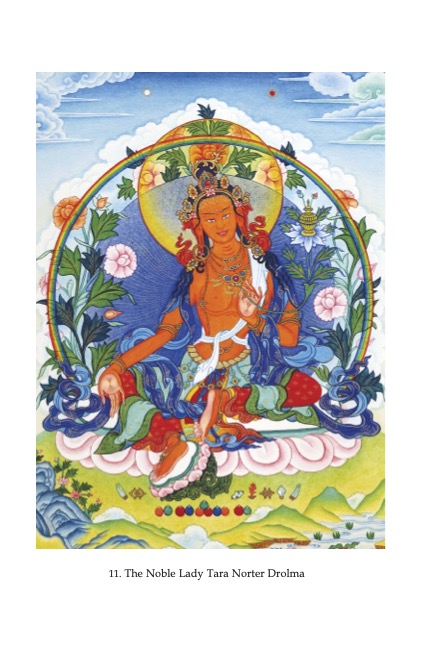

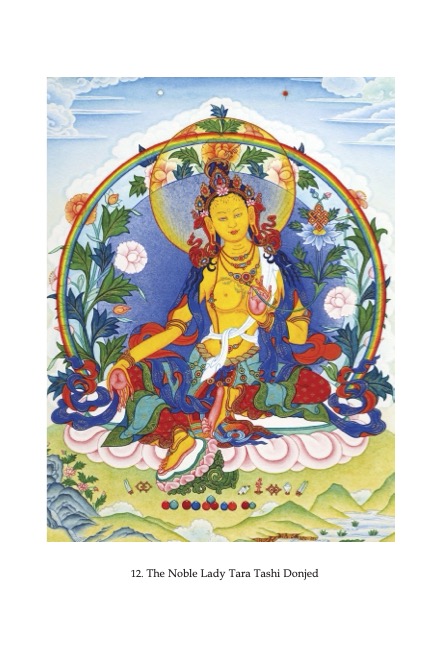

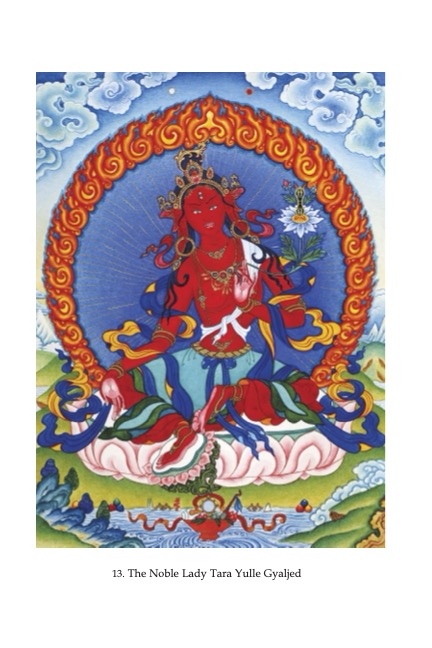

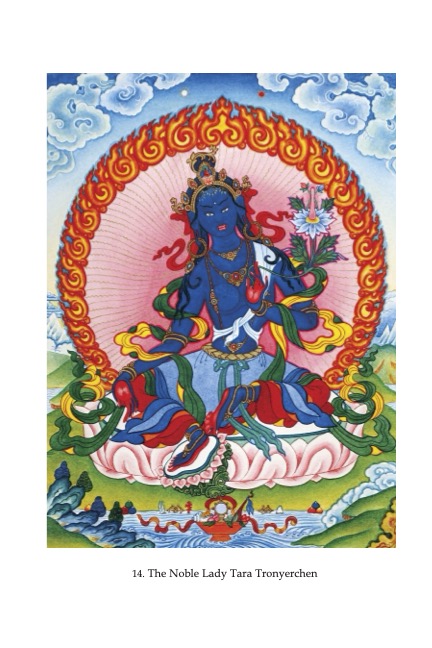

Name and Attributes of Her Twenty-one Emanations

| Name of Tara* | Her Color | Her Hand Object | Her Activity according to Outer Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nyurma Pamo | red | conch shell | swift, heroic liberation from sufferings |

| 2. Loter Yangchenma | white | mirror | sound of peace, harmony, truth, and wisdom |

| 3. Sönam Tobché | golden | wish-fulfilling jewel | increases merit and prosperity |

| 4. Tsugtor Namgyalma | golden | nectar vase | increases life force and longevity |

| 5. Wangdü Rigié Lhamo | red | bow and arrow | magnetizes beneficial wisdom essences |

| 6. Jigjé Chenmo | dark red | phurba/dagger | subdues invisible beings, mental disturbances |

| 7. Zhengyi Mithubma | blue-black | flaming sword | destroys internal and external artifices |

| 8. Zhengyi Migyalma | dark red | flaming vajra | destroys maras, subdues illusions |

| 9. Sengdeng Nagchi | green | dharma wheel | protects from all outer and inner fears |

| 10. Jigten Sumlé Gyalma | rich red | victory banner | subdues worldly distractions, arrogance |

| 11. Phagma Norter Drolma | orange-red | treasure vase | gives wealth, removes sufferings of poverty |

| 12. Tashi Donjé | gold/yellow | infinite knot | inner and outer balance, timely seasons, harvests |

| 13. Yallé Gyalma | dark red | open vajra | stops warfare, enmity; heals destruction of anger |

| 14. Thronyer Chen | blue/black | tung shing/pestle | crushes subtlest negativities and obstacles |

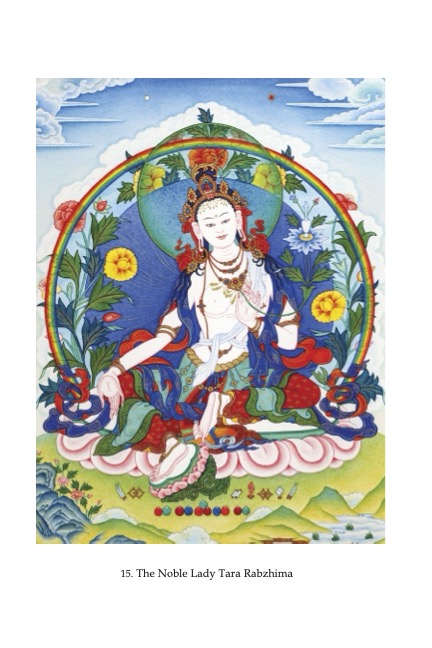

| 15. Rabhima | rich white | small vase | purifies greatest evils and obscurations |

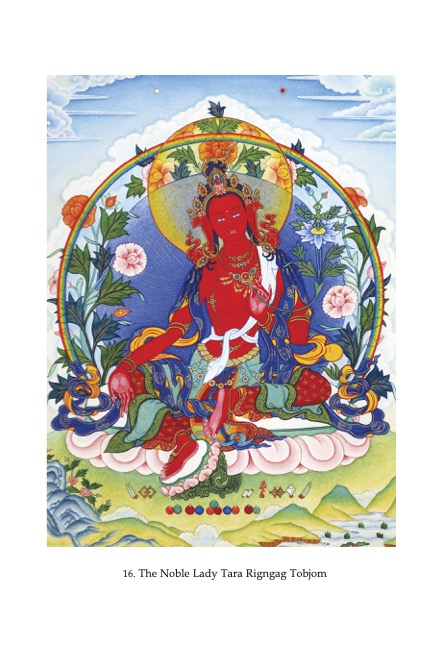

| 16. Rigngag Tobjom | red | double dorje | destroys bad intentions and their source, ego |

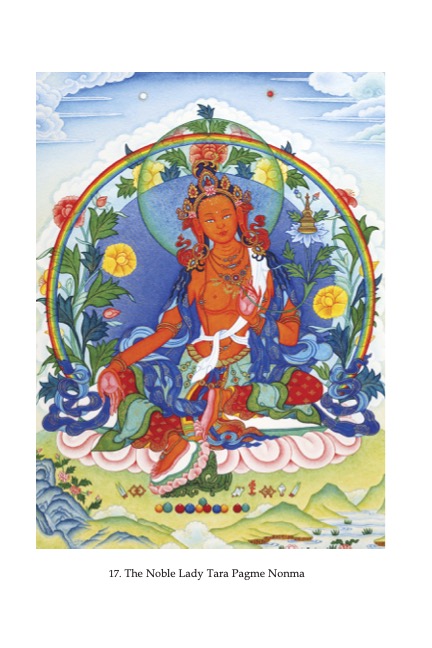

| 17. Pagmé Nonma | orange | golden stupa | stops violent activites such as robbery, hunting |

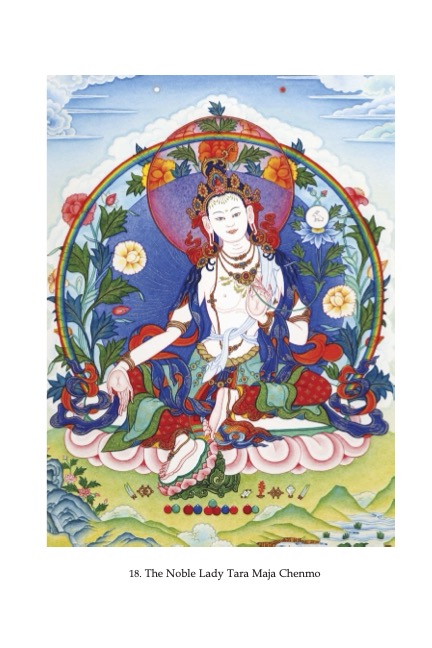

| 18. Maja Chenmo | white | rabbit-marked moon | protects against outer and inner poisons; protects infants and children |

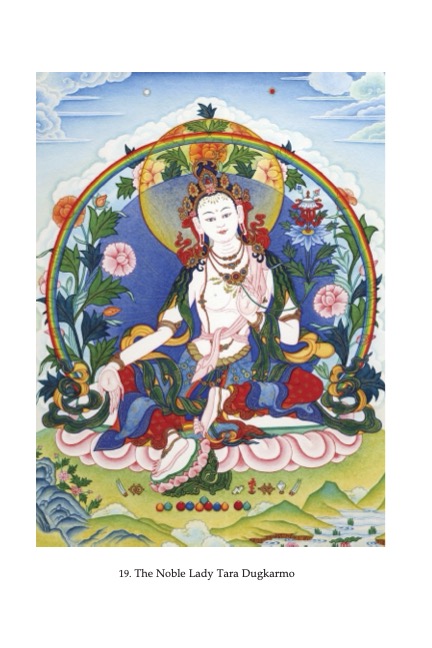

| 19. Dugkarmo | white | white umbrella | protects from nightmares, disputes, curses |

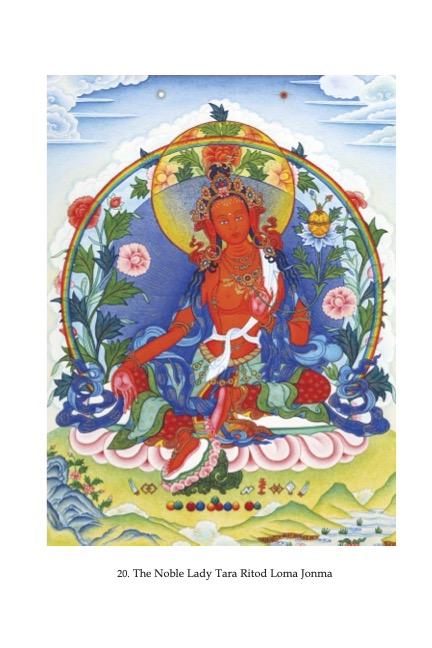

| 20. Rito Loma Jonma | saffron | za ma tog | dispels epidemics and deadly illness |

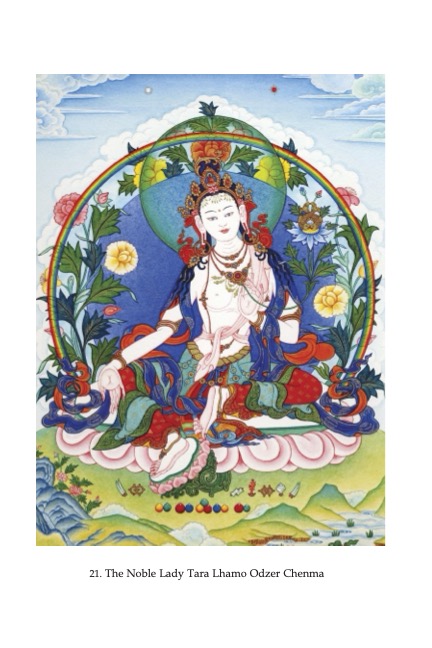

| 21. Lhamo Ozer Chenma | white | golden fish | protects life force, brings inner radiance;protects animals |

* Each name is prefixed by an honorific title, either Jetsün Drölma or Noble Lady Tara.