Through the inspiration and blessing of our Guru comes realization of the Four Noble Truths. Thus our realization of the Noble Truths is the inspiration and blessing of our Guru. To be shown the Four Noble Truths is not realization, that requires wisdom.

Guru Yoga

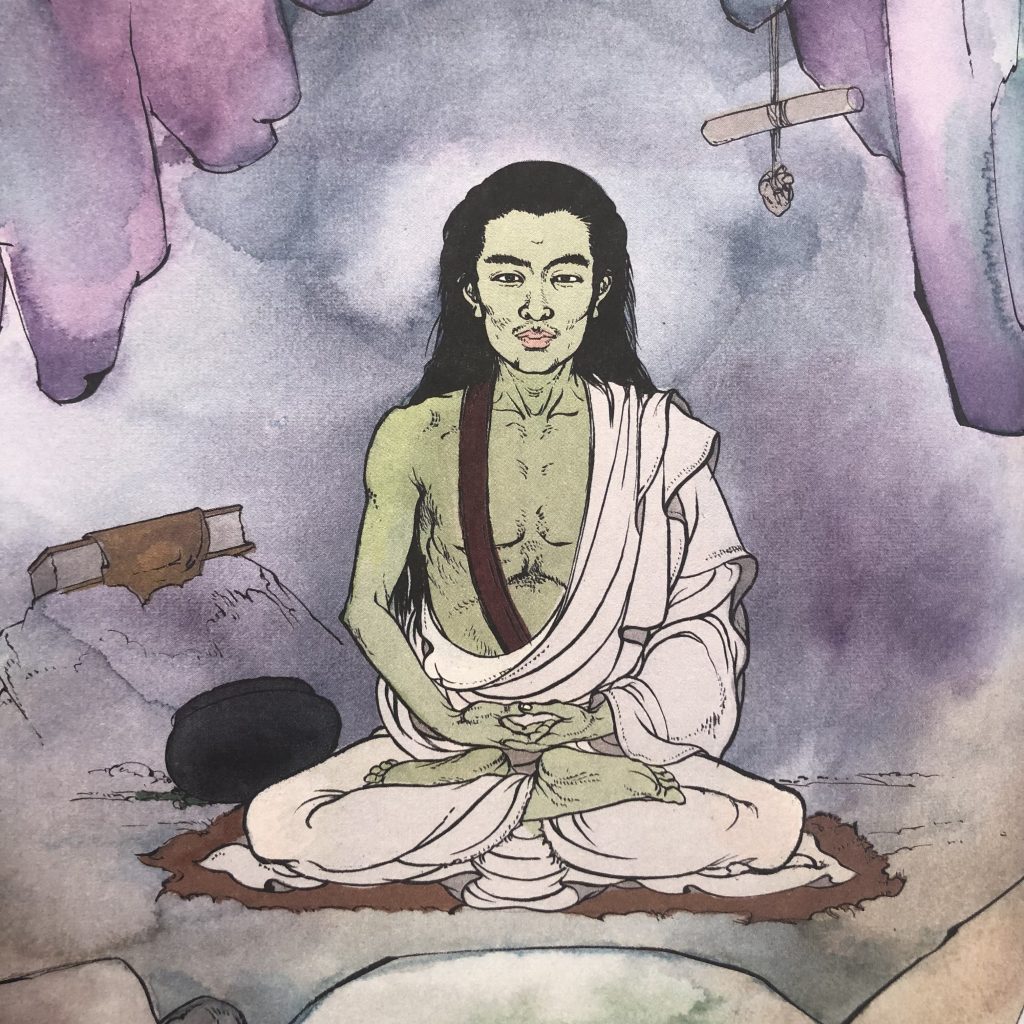

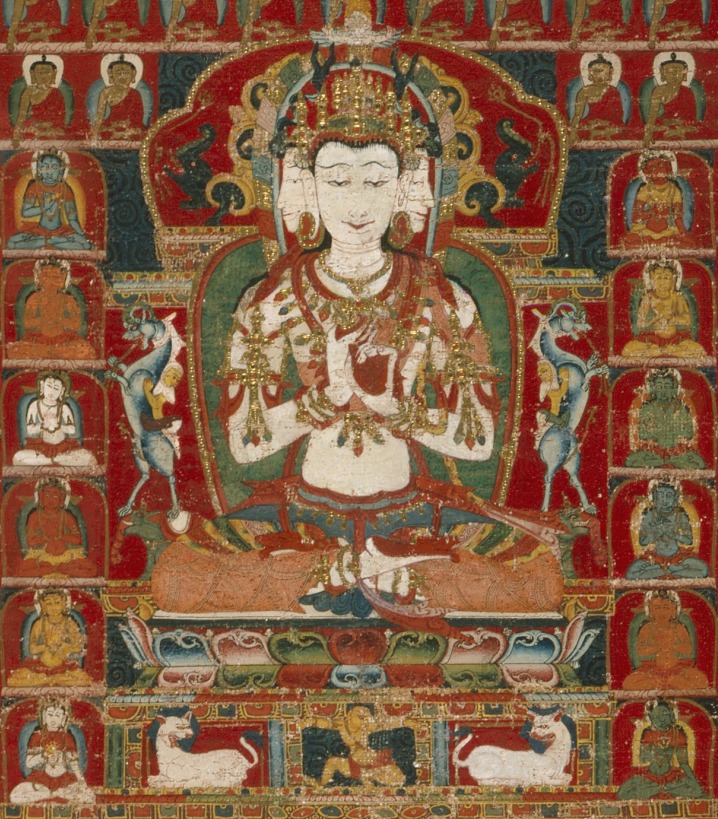

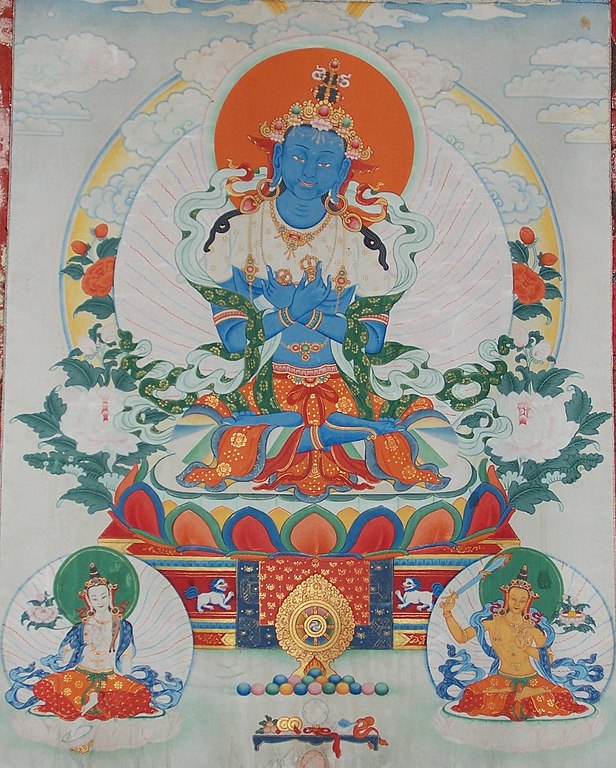

In meditation, visualize the essence of your Guru as Vajradhara, a tantric aspect of Shakyamuni Buddha, as manifested in the non-dual space before you.

Vajradhara (‘holder of the vajra’) is an expression of the Dharmakaya and root of all the enlightened-families. The vajra (Tibetan: dorje) is a diamond (‘sovereign among all stones’) scepter-like ritual object that indicates the indestructible reality of buddhahood. The vajra and bell together represent the perfect union of discriminative awareness and skillful means.

In appearance, Guru Vajradhara, radiant blue in color, sits upon a throne supported by eight snow lions atop a lotus and sun seat. He holds a vajra and a bell and embraces his blue consort. Their blue spatial radiance is great bliss and wisdom of non-duality. Recognize it as such.

At their crown chakra visualize a white om atop a moon seat, at their throat chakra a red āh atop a red lotus, and at their heart chakra a blue hūm atop a sun. They have great kindness and concern for you.

Light radiates in the ten directions from the hūm at Guru Vajradhara‘s heart. Atop each ray you may visualize one of the lamas who have mastered the practice of inner fire yoga and have realized the illusory body and wisdom of clear light.

Preform the seven-limb prayer (below) with mandala offering. The best offering to give is the offering of meditation practiced sincerely toward happiness and realization.

Pray intently to Guru Vajradhara, the Dharma protector, for realization according to the development of your practice.

Visualize all the lineage lamas as they dissolve into Guru Vajradhara.

From Guru Vajradhara, emanating rays of:

- white light from the om at his crown chakra enters yours

- red light from the āh at his throat chakra enters yours

- blue light from the hūm at his heart chakra enters yours

Visualize as Guru Vajradhara absorbs into you at your crown, enters into your central channel and into your your heart chakra. Unify your body and speech with those of Guru Vajradhara. Unify your mind with Guru Vajradhara’s transcendental, blissful wisdom of dharmakaya.

If you have a dualistic conceptual view of Guru Vajradhara you do not comprehend.

Recognize the guru in every moment.

Seven Limbed Prayer Before those of great compassion we lay bare with mind of regret all non-virtuous actions of misfortune committed since beginning-less time or have caused others to commit or have rejoiced in, we vow never to commit again. All things are like a dream, lacking inherit or natural existence, sincerely we rejoice in the happiness and joy of all Āryas and non-Ārya beings and in ever white arisen virtue. May the rains of vast profound Dharma fall From a hundred thousand billowing clouds of sublime wisdom and loving-compassion, to nurture, sustain and propagate a garden of moon flowers for the benefit and bliss of infinite beings. Your vajra-body subject to neither birth nor death is a vessel of Unity’s wish-granting gems, Please abide forever in keeping with our wishes: Pass not into nirvāna until samsāra’s end. We dedicate white virtues created that we may be inseparably protected throughout all our lives by venerable Gurus possessing the three kindnesses and that we may attain Vajradhāra Unity.