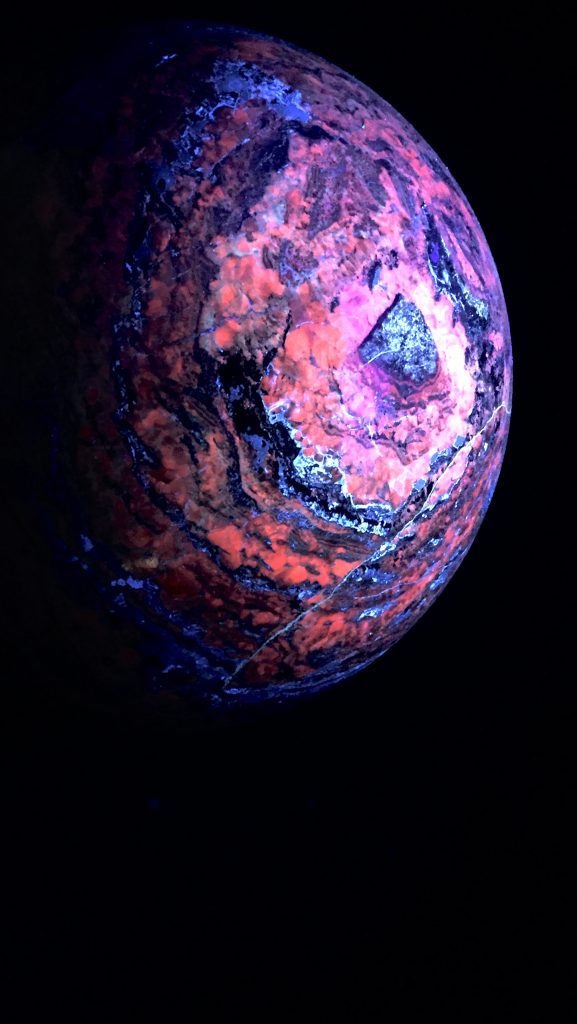

WOA: Metamorphia, Smallest Natural Satellite of Ced’a-meon

Ideas realized

Like breath in the wind,

the disillusioned see not

the three gems within.

Profess how I long,

Through metered song

To rhythmic tick and every tock

Of celestial cosmic clock,

That counts by years,

A turning golden gear,

For thy scared kiss,

Beloved, Eurydice,

Veiled by chimeric myst

Of the depths of hell,

Where twice you fell.

Forever together in heart,

Ever in temporal plane apart.

Reflections during a summer solstice… Content in the realization that the declination of my Earthly Sol now travels north, toward final winter’s hibernation. To what point oratory hyperbole and grandiloquence bombast? Magniloquence verbosity with pomposity elocution? Eloquence replaced with rant and discourse, and oration displaced by balderdash fustian frustration. Waxing exclusive warring tribes, and inkish snide eclipsing waning inclusive benevolent compassion. You know not me, nor I any more learned of you. Where does humanity hide?

The keen

concede

their ignorance.

From: The Dhammapada: Cittavagga (The Mind) 33. Just as an arrow-maker straitens an arrow shaft, even so the discerning person straitens his mind- so fickle and unsteady, so difficult to guard and control. 36. Let the discerning person guard their mind, so difficult to detect and extremely subtle, wandering wherever it desires. A guarded mind brings happiness. 43. Neither mother, father, nor any other relative can do one greater good then one’s own well-directed mind. Thus said the Blessed One.

From: A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life.

By: Shantideva.

I. The Benefits of the Awakening Mind

4. Leisure and endowment are very hard to find;

And, since they accomplish what is meaningful for humanity,

If I do not take advantage of them now,

How will such a perfect opportunity come about again?

8. Those who wish to destroy the many sorrows of (their) conditioned existence,

Those who wish (all beings) to experience multitude of joys,

And those who wish to experience much happiness

Should never forsake the Awakening Mind.

15. In brief, the Awakening Mind

Should be understood to be of two types;

The mind that aspires to awaken

And the mind that ventures to do so.

25. This intention to benefit all beings,

Which does not arise in others even for their own sake,

Is an extraordinary jewel of the mind,

And its birth is an unprecedented wonder.

36. I bow down to the body of those

In whom the sacred precious mind is born.

I seek refuge in that source of joy

Who brings happiness even to those who bring harm.

III. Full Acceptance of the Awakening Mind

4. And with gladness I rejoice

In the ocean of virtue, for developing an Awakening Mind

That wishes all beings to be happy,

As well as in the deeds that bring them benefit.

24. Likewise, for the sake of all lives

Do I give birth to an Awakening Mind,

And likewise shall I, too,

Successfully follow the practices.

28. Just like a blindman

Discovering a jewel in a heap of rubbish,

Likewise, by some coincidence,

An Awakening Mind has been born within me.

From: Eight Verses for Training the Mind By: Kadampa Geshe Langritangpa 5. In all actions may I watch my mind, And as soon as disturbing emotions arise, May I forcefully stop them at once, Since they will hurt both me and others.

Bodhicitta (Sanskrit) (Tibetan: byang chub kyi sems): An altruistic aspiration to attain full enlightenment for all beings. Bodhicitta is cultivated on the basis of certain mental attitudes, principle among them being the development of love and great compassion towards all beings equally.

From: The Handbook of Tibetan Culture, 1993.

Compiled by Graham Coleman