Seda

Cruz Rincon

Eternity Seas’ Reality

End of the Pier

Azul en Azul

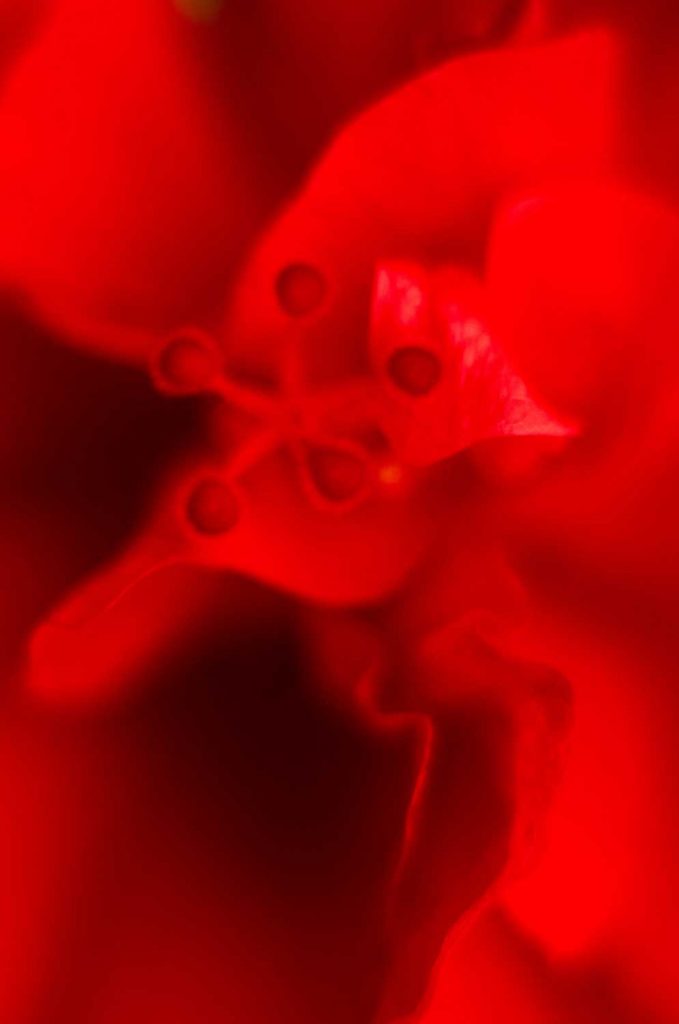

Tiano y Flor

[Buddy] Free[s] Guy

From Free Guy (film, 2021)

GUY: Buddy, what would you do if you found out that you weren’t real? … BUDDY: I say, okay, so what if I’m not real? GUY: I’m sorry. “So what?” BUDDY: Yeah. So what? Guy: (SCOFFING) But if you’re not real, doesn’t that mean that nothing you do matters? BUDDY: What does that mean? Look, brother, I am sitting here with my best friend, trying to help him get through a tough time. Right? And even if I’m not real, this moment is. Right here, right now. This moment is real. I mean, what’s more real than a person tryin’ to help someone they love? Now, if that’s not real, I don’t know what is.

Uncertainly Certain

“Teacher, you say, “What is to one may not be to another, and what is not to one may be to another.” Could you elaborate on the meaning of this?”

“All things are inherently empty, dependent on conditioning, and interdependently conceptualized. Thus there is subjective variance in conceptual existence of a thing, as all things are of parts. If you were to add water one drop at a time to an empty glass, when would it be considered full? When an observer recognizes it as full.”

The student sat in reflection, after some time he replies,

“In sea of thoughts

my mind swims.

Not any one of them,

Nor any me.

But what you see.”

“Good. Good. Very good.”

Ryuichi Sakamoto

Adagio from Sakamoto’s album “Beauty”